Recognizing replacement and first calf heifers need extra management, producers take different paths to get to the same destination.

Beef producers like Darren Bevans in Alberta, Tyler Fulton in Manitoba and Murray Shaw in southwest Ontario know that replacement and first calf heifers need some extra attention, especially heading into and over winter — the heifers are not only pregnant and about to produce calves, but these young females are still growing themselves.

Beef producers like Darren Bevans in Alberta, Tyler Fulton in Manitoba and Murray Shaw in southwest Ontario know that replacement and first calf heifers need some extra attention, especially heading into and over winter — the heifers are not only pregnant and about to produce calves, but these young females are still growing themselves.

The “extra attention” doesn’t require over the top management, but just paying attention to feed and weather conditions to ensure heifers maintain a proper body condition to meet the nutritional requirements of the unborn calf as well as to support their own body growth.

In their respective operations, with extended fall and winter grazing programs, Bevans and Fulton manage heifers separate from their main cowherds so that heifers can be given extra feed when necessary. In Ontario come early December, Shaw moves the whole herd onto full feed using a Total Mixed Ration (TMR). The hay and corn silage ration is formulated so it meets requirements to keep heifers in good condition. It may be a bit more than the mature cows actually need, but adequate to meet heifer requirements.

Heifers aren’t as competitive as cows especially in limit feeding situations on swaths, corn grazing, or bale grazing. Even in drylots competition can be issue around feed bunks and round-bale feeders. And when the weather gets particularly cold it is important to meet the energy requirements of these young females to ensure their body condition doesn’t slip. For every 1 C drop in temperature below 0 C, the beef cow’s TDN energy maintenance requirements are increased by about two per cent. Nutritional requirements, just due to the demands of cold temperatures, increase by 25 to 30 per cent over winter.

- The Alberta Agriculture website has more information about adjusting feeding during cold weather at http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/faq7955

Proper nutrition and growth is important with heifers to ensure optimum reproductive performance. Research shows beef heifers should be at 60 to 65 per cent of their mature weight at about 14 months of age, at 65 to 70 per cent of mature weight at time of first breeding (15 months of age) and 85 to 90 per cent of mature weight at time of calving (24 months of age). Heifers continue to grow even through to their second calving.

There is well-researched and documented evidence showing the cost if cows and heifers are in poor or thin condition.

If you have skinny or poor condition animals heading into winter, that December to March period is probably one of the toughest and most expensive times to try to get them back into condition, say researchers and ranchers, alike. And if they are on the poorer side heading into calving, then calving difficulties can increase, weaker and low vigour calves can result, and after that the costs and management mount trying to get those mothers back into condition for the approaching breeding season.

The economic value of keeping heifers and the cow herd in good condition heading into winter, to calving and to next year’s breeding season is considerable. Some research comparing cattle with the mid-range (recommended) body condition score versus a low body condition score, showed the mid-range cattle had 10 per cent more live calves, calf weaning weights the next fall were 26 per cent higher, and the pregnancy rate among mid-condition cows came in at 92 per cent versus 79 per cent for lower condition females.

It is important that producers remember and manage for the fact that heifers aren’t just young cows, says Bart Lardner, senior research scientist at the Western Beef Development Centre (WBDC) in Saskatchewan.

“Bred and first-calf heifers are still growing themselves,” says Lardner. “So they shouldn’t be managed the same as mature cows.” In fact, he says heifer management is actually a three-year project.

“Sometimes producers will manage those replacement heifers really well from weaning until the time they are bred, and as soon as they have that first calf they get moved into and managed with the cow herd,” says Lardner. “But that heifer herself is still growing so has higher feed requirements. She needs to be managed properly right through until that second calving. Producers have a lot invested in these heifers and they need to be managed properly.”

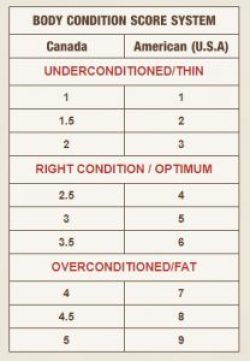

Ideally producers should apply Body Condition Scoring (BCS) to entire beef herd, says Lardner. Canada has a five point BCS scale — one being thin and five being fat. Some producers apply the U.S. nine-point BCS system rating cattle on a scale from one to nine.

Ideally producers should apply Body Condition Scoring (BCS) to entire beef herd, says Lardner. Canada has a five point BCS scale — one being thin and five being fat. Some producers apply the U.S. nine-point BCS system rating cattle on a scale from one to nine.

An excellent video and more information on condition scoring is available at: www.bodyconditionscoring.ca.

Older research has suggested that heading into and over winter cows and heifers should be fed to maintain at 2.5 to 3 score on the Canadian BCS, which is about five on U.S. scale. More recent research, which studied over 100 herds across Western Canada, found that open rates are lowest in females with a BCS of 3.0 to 3.5 on the Canadian scale.

The challenge with feeding bred and first calf heifers is they require more energy, protein and other nutrients comparatively to mature cows, yet have about 20 per cent less dry matter capacity (eat less). In more situations than cows, heifers cannot physically eat enough poor quality feed to meet their needs.

“If a mature animal is being maintained on ration containing eight to 10 per cent protein, for example, the bred heifers and first-calf heifers are going to need about 20 per cent more,” says Susan Markus, beef research scientist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.” And energy requirements will be similar. If the cow ration has 55 per cent TDN, the heifer ration needs to be in 60 to 65 per cent TDN range.”

She urges producers to pay attention to feed quality whether it is baled hay or cereal swaths, or other winter feed. Poorer quality, high fibre forage may fill cattle up but still not meet their nutrient requirements. And she also recommends cattle be provided a well balanced mineral mix. Cereal-based feeds, for example can be high in potassium, which can adversely affect calcium levels in cattle.

Research shows it takes more feed (higher cost) to improve body condition of a beef animal in winter, so it makes good economic sense to have replacement and first calf heifers in good shape heading into late fall and winter feeding. (With a 1,200 pound mature animal, for example, it takes about 160 pounds of weight gain to improve body condition score by one point (on the Canadian scale) – feed costs to achieve that add up).

Depending on summer and fall pasture quantity and quality, it may make sense to wean first calf heifers — nursing heifers also pregnant with their second calf — about a month early so they are not trying to still feed a calf and can use available nutrition for their own body growth.

Replacement and first calf heifers can do well on fall and winter extended grazing programs, they just need to be properly managed says Lardner.

“Sure the risk is there that cattle can lose condition on swath, bale grazing and other winter feeding systems,” he says. “But it is also quite manageable. You have to apply the proper management, but there is no reason these systems can’t work, maintain cattle in good body condition, and in fact we have seen situations were they actually gain weight while winter grazing.”

“Sure the risk is there that cattle can lose condition on swath, bale grazing and other winter feeding systems,” he says. “But it is also quite manageable. You have to apply the proper management, but there is no reason these systems can’t work, maintain cattle in good body condition, and in fact we have seen situations were they actually gain weight while winter grazing.”

Lardner says the first step, whether it be with barley, oats, triticale swaths, for example, bale grazing or corn grazing, is to have a feed test analysis completed before cattle start grazing, so producers know if there are any limiting quality factors.

If you use your eyes to predict the quality of that feed stuff, then you could be in a deficient position, suggested Lardner. “So have it tested.” Many forages saved for winter feed might look good but they could be low on protein, or they could be low on energy which is particularly important heading into those coldest days of winter, he says. So know your feed quality and be prepared to provide a supplement if key nutrients are lacking.

He says also remember cows and heifers need to be on a higher plane of nutrition during the last trimester of pregnancy. “If you have different qualities of stockpiled feed put them on the lower quality feed, such as straw or chaff, earlier in the winter grazing period and then switch them over to higher quality feed as they approach calving.”

If animals are under-conditioned, feeding lower quality feed earlier in the winter is not a good option, and adjustments to the feeding program should be made no later than 60 days before calving.

When swath-grazing, animals given free range will eat the seed heads first and be left with nothing but stems and stalks later in the winter when it’s colder and nutrient requirements are higher, so cross-fencing and restricting access are critical (and also reduces wastage).

Lardner also recommends first and second calf heifers be fed separately from mature cows. Those heifers have higher nutrient requirements than mature cows so it is important their winter feed is meeting those requirements.

He says replacement and first calf heifers don’t have to be babied in a drylot with high quality feed. He says don’t be afraid to put them out on swath or corn grazing or bale grazing with supplements as needed. They can do very well with a well-balanced swath-grazing ration, and then become very efficient animals later in the cow herd.

MURRAY SHAW

BEAR CREEK FARM

BRIGDEN, ON

Murray Shaw delays breeding of predominately straight blood Limousin replacement heifers so they are calving at 27 to 30 months of age on his southwest Ontario farm.

Running about 100 head of females in a herd that is 50 per cent purebred and 50 per commercial, Shaw says he’s found delaying breeding improves reproductive performance down the road. “Not everyone agrees with me, but I find these Limousin cattle are slower to mature,” he says. “If I delay the first breeding of replacement heifers by three to six months, the first-calf heifers are much easier to get rebred.”

Depending on the year, as fall pasture quantity and quality declines he may need to supplement pasture with hay before moving cows and heifers to the well-bedded yard with shelter. They are put on a full feed Total Mixed Ration for the winter. He did use round bale feeders for a number of years, but found it wasn’t very efficient and the heifers had a hard time competing with mature “boss” cows. For the past nine years he’s been feeding the TMR of hay and corn silage at a feed bunk. “They all have plenty of space and easy access to the ration,” he says.

Shaw says he does pay attention to body condition, with a year-round objective to make sure nothing gets out of condition. With year-round calving in three batches — a winter group calving between January and March, a spring group calving between April and June and a fall group calving between August an October — he aims to keep cows and heifers in the 2.5 to 3 body condition score range.

If pasture quality declines he supplements with hay and “ the TMR can be easily adjusted as needed,” he says. The TMR is formulated to meet the requirements of heifers, which may be a bit more than the mature cows need, but they don’t appear to be over conditioned either,” he says.

DARREN BEVANS

DESERET RANCHES

RAYMOND, AB

In managing for year-round grazing at Deseret Ranches in southern Alberta, Darren Bevans says first and second calf heifers are managed separately from the cowherd on winter swath grazing.

“Managing these groups separately allows us to provide a little bit of extra nutrition, which can make all the difference to body condition and future pregnancy rates” says Bevans. “Really these bred heifers are treated much like the mature cowherd, except that they will be supplemented with some quality alfalfa hay or pelleted supplement when conditions require it. ”

In winter, Deseret bred heifers are managed in a large herd of more than 1000 head, with limit access to swaths using electric fence. Heifers have access to between five and seven days worth of swathed feed at time.

“Of course on the first day or two they are eating the best part of the swaths and then as the days go on they are getting down to the less preferred material,” he says. “So if they are on this area for seven days, for example, on about day five we give them some alfalfa hay as a supplement. Depending on weather and temperature conditions we can adjust the amount of supplemental feed provided.” In case of conditions where swaths become unavailable or where weather becomes too severe Deseret Ranches is prepared to provide a full feed hay ration.

Winter herd management does involve visual body condition scoring on a weekly basis. Following the nine-point U.S. system he aims to see the herd maintained at a five condition score (roughly equivalent to a score of 3, on the 5 point Canadian system). If it looks like any group is starting to slip, extra nutrition is provided.

With heifers weaned early ahead of the mature cowherd, all cattle remain on pasture into early winter and usually move onto swath grazing on straight oats and triticale swaths in late December or January.

TYLER FULTON

BIRTLE, MB

Tyler Fulton, Birtle, MB

Tyler Fulton admits he prefers to baby the replacement and first calf heifers a bit over winter on his southwest Manitoba farm at Birtle, near the Saskatchewan border.

The full Beef Booster/cross cowherd and heifers usually remains on pasture until late November when females are weaned and preg checked. The cowherd then moves onto oats and barley swaths for a few weeks of transition from pasture before being moved in mid to late December into corn grazing for about three months.

As the cows remain out, the replacements and some of the first-calf heifers are moved into a 20-acre paddock with shelter and portable feed bunks and put on feed. Steer calves are moved into a background program.

“I probably baby the heifers a bit but I’m not sure how well they will compete with the mature cows in corn grazing,” says Fulton. He applies a visual condition scoring to the herd, aiming to maintain everything at the 2.5 to 3 condition score over winter.

Heifers on the 20-acre paddock are supplied a ration that includes both corn and alfalfa silage, along with alfalfa hay as needed.

Photo courtesy of Tyler Fulton

“Since first-calf heifers are still growing as well we do a sort with them at weaning,” says Fulton. “Anything that is a bit smaller or could use more condition goes with the replacement heifers into the winter paddock, while the others will stay with the cows. If we have 80 to 90 replacement heifers, for example, we may be feeding 110 head in the paddock over winter — the rest being the first-calf heifers.”

Fulton says the silage and/or hay ration in the paddock maintains the heifers in that excellent mid-range condition, with few calving problems as the heifers start calving in April, followed by excellent conception rates at rebreeding.

- More information on the value of body condition scoring is available at: www.bodyconditionscoring.ca

Click here to subscribe to the BCRC Blog and receive email notifications when new content is posted.

The sharing or reprinting of BCRC Blog articles is welcome and encouraged. Please provide acknowledgement to the Beef Cattle Research Council, list the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you chose to share the article by emailing us at info@beefresearch.ca.

We welcome your questions, comments and suggestions. Contact us directly or generate public discussion by posting your thoughts below.

Source: Latest from Beef Cattle Research Council